When the first computer programs were created the world faced the question: how should we protect them? The choice was basically between two already existing and very different types of protection: copyright and patent protection.

I. CHOICE BETWEEN PATENT AND COPYRIGHT PROTECTION

At first sight, the patent might seem like a more intuitive and adequate form of protection. After all, we’re talking about a creation that we perceive as highly technical. And, normally, the technical creations are protected as patents, not as copyrights, which we associate more with aesthetic creations.

On the other hand, when we look deeper, it’s noticeable that patents protect certain technical solutions that we call inventions, such as the hardware, construction of a telescope etc. And software may not be that obviously considered an invention.

Some acknowledge its technical value, based on the functionalities it brings to life. However, from another point of view, the software is often believed not to introduce (usually) any new technical solution of a technical problem per se. It’s because, for example, software that allows playing music or displaying images (and, therefore, processing them) does not invent anything really new, because the system of processing is already known. In that case, the software may be considered as a new expression of the existing type of work: written in a certain new, original way, by the programmer.

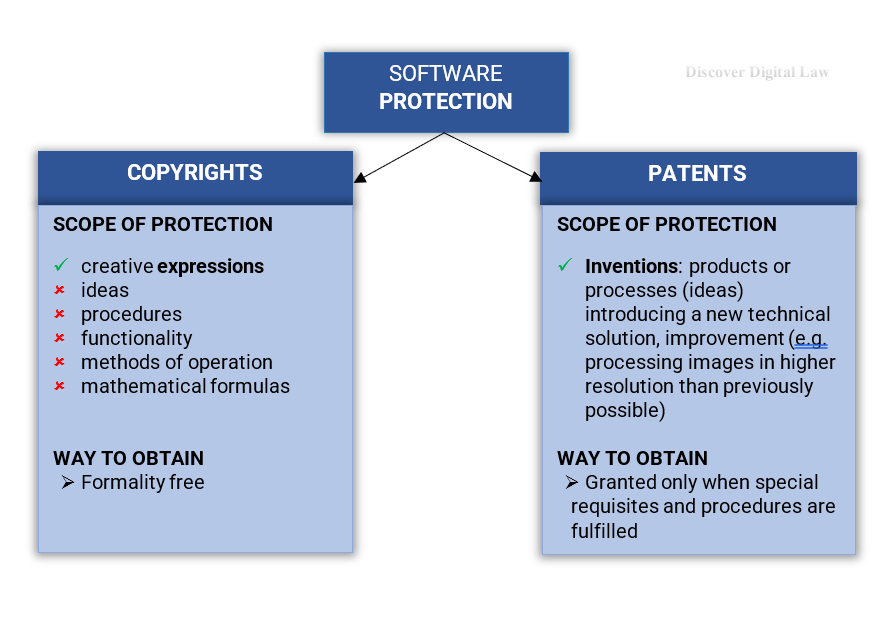

Furthermore, both types of protection bring different results. In particular, patents protect original ideas (inventions, technical solutions): a set of instructions of how to resolve a technical problem. And in order to protect such inventions, it’s necessary to register them complying with certain formal procedures and strict requisites. On the other hand, copyright law protects original expressions of the ideas, such as the original (creative) way a set of instructions is written, the original way a picture is painted, the original composition of (even not) original elements. This kind of protection usually does not require complying with any formalities and it is often granted automatically.

In this context, it’s worth noticing that, if we put it simply, there may be only one idea of the exact same functionality but there may be many ways to express that idea. Consequently, protecting the idea itself (by patents) and not only its expression (by copyright) naturally broadens the scope of protection (in favour of the idea’s creator) and limits other developers. That’s why protecting software through patents may impede innovation.

II. COPYRIGHT PROTECTION OF COMPUTER PROGRAMS IN EUROPE

A. Law

Computer programs were introduced to the international copyright agreements (and, precisely, to the Berne Convention with the amendment in 1971 and the TRIPS agreement signed in 1994) as a literary work.

The European Union followed that line. Consequently, as a general principle, in Europe, computer programs are protected by copyright law as literary works.

The first EU law which introduced and governed the protection of computer programs in 1991 was Directive 91/250 EC on the legal protection of computer programs. That Directive has been replaced by Directive 2009/24 EC on the legal protection of computer programs (the ‘Computer Programs Directive’), implemented in the EU Member States.

B. Subject of protection

The crucial question about the copyright protection of computer programs is: what is actually protected? The code itself (and, therefore, the sequence of commands, as the developer sees it) or the effect of the code (and, therefore, the visual effect and functions perceived by the user)?

Normative references

The copyright laws may give us some idea.

- Art. 1 para. 2 of the Computer Programs Directive: ‘Protection in accordance with this Directive shall apply to the expression in any form of a computer program. Ideas and principles which underlie any element of a computer program, including those which underlie its interfaces, are not protected by copyright under this Directive’.

- Art. 6 co. 1 of the Computer Programs Directive ‘The authorisation of the rightholder shall not be required where reproduction of the code and translation of its form within the meaning of points (a) and (b) of Article 4(1) are indispensable to obtain the information necessary to achieve the interoperability of an independently created computer program with other programs’.

- Recital 7 of the Computer Programs Directive: ‘For the purpose of this Directive, the term “computer program” shall include programs in any form, including those which are incorporated into hardware. This term also includes preparatory design work leading to the development of a computer program provided that the nature of the preparatory work is such that a computer program can result from it at a later stage’.

- Recital 8 of the Computer Programs Directive: ‘In respect of the criteria to be applied in determining whether or not a computer program is an original work, no tests as to the qualitative or aesthetic merits of the program should be applied‘.

- Recital 15 of the Computer Programs Directive: ‘The unauthorised reproduction, translation, adaptation or transformation of the form of the code in which a copy of a computer program has been made available constitutes an infringement of the exclusive rights of the author. Nevertheless, circumstances may exist when such a reproduction of the code and translation of its form are indispensable to obtain the necessary information to achieve the interoperability of an independently created program with other programs. […] Such an exception to the author’s exclusive rights may not be used in a way which prejudices the legitimate interests of the rightholder or which conflicts with a normal exploitation of the program’.

- Article 10 para. 1 of the TRIPs Agreement: ‘Computer programs, whether in source or object code, shall be protected as literary works under the [Berne Convention].’

Based on the above normative references it seems clear that the subject of protection is precisely the code and not the effect it produces (and, therefore, not the computer program as the user perceives it but the lines of the code written by the programmer).

CJEU interpretation

The above interpretation has been confirmed by CJEU.

The subject of protection of computer programs was considered for example in the CJEU case C-406/10, SAS Institute vs World Programming Ltd. In that case, the Court ‘concluded that the source code and the object code of a computer program are forms of expression thereof which, consequently, are entitled to be protected by copyright as computer programs, by virtue of Article 1(2) of Directive 91/250. […]. In that context, it should be made clear that, if a third party were to procure the part of the source code or the object code relating to the programming language or to the format of data files used in a computer program, and if that party were to create, with the aid of that code, similar elements in its own computer program, that conduct would be liable to constitute partial reproduction within the meaning of Article 4(a) of Directive 91/250′.

Furthermore, the Court confirmed that ‘the functionality of a computer programme and the programming language cannot be protected by copyright‘. It further specified that ‘to accept that the functionality of a computer program can be protected by copyright would amount to making it possible to monopolise ideas, to the detriment of technological progress and industrial development’.

Conclusions

Based on this judgement it seems, therefore, that it is ok to study how the program functions and then to write your own program to emulate that functionality. It’s not ok to copy (reproduce) the code (unless made in compliance with art. 6 co. 1 of Directive 2009/24 and other general exceptions provided by the law).

It’s worth noting that the above-mentioned sentence refers to the functionality of the program and not to its visual effects, and, therefore, the general layout of the program, all the photos, contents etc. used therein. The fact they are not protected exactly by the Computer Programs Directive does not exclude their protection based on general rules of copyright laws. So, before copying someone’s software to the minimum details, hold your horses and reflect if it may infringe copyrights connected with the layout and the content of the program.

III. PATENT PROTECTION OF COMPUTER PROGRAMS

While the computer programs in the EU are expressly protected by copyright law, the Computer Programs Directive, in art. 8, states that ‘the provisions of this Directive shall be without prejudice to any other legal provisions such as those concerning patent rights, trade-marks, unfair competition, trade secrets, protection of semi-conductor products or the law of contract’. Therefore, the Computer Programs Directive acknowledges the possibility of protecting software also through patents.

On the other hand, computer programs per se are expressly excluded from the patent protection by art. 52 para. 2 of the European Patent Convention. According to that paragraph the ‘following in particular shall not be regarded as inventions within the meaning of paragraph 1: (a) discoveries, scientific theories and mathematical methods; (b) aesthetic creations; (c) schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, playing games or doing business, and programs for computers; (d) presentations of information’.

On the other hand, paragraph 3 then says the ‘provisions of paragraph 2 shall exclude patentability of the subject-matter or activities referred to in that provision only to the extent to which a European patent application or European patent relates to such subject-matter or activities as such‘.

Therefore, notwithstanding the seemingly clear exclusion of computer programs from patent protection in paragraph 2, the software may be registered and protected as a patent when it meets the regular requirements of a patent. Therefore, to be a patent it must introduce a new technical solution to a technical problem.

IV. COMMENT

In Europe, the prevailing regime is protecting the computer programs by copyright law. It is good news for the EU innovation startups. In fact, it gives lower chances of infringing the patents of other developers and decreases the costs relating to the relevant formalities and lawyers.

On the other hand, the EU companies moving, for example, to the US must remember they still may be sued there by the Americans who are allowed to patent their software (to some extent). Consequently, when opening shops overseas, it’s worth verifying all the third-party IP rights that we may infringe and activating the relevant protection, especially by registering our patent if it’s eligible for protection.